The Federal Circuit recently issued an opinion in the case In re Owens affecting the range of permissible claim changes in design patents. In re Owens, Appeal No. 2012-1261 (Fed. Cir. Mar. 26, 2013). Unlike utility patents, where the claims are defined by words, in design patents, the claims are set forth in drawings illustrating the claimed ornamental design. The In re Owens case is an appeal from a decision by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s (USPTO) Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences (BPAI), and the case turned on whether specific aspects of the drawings in the design application at issue were supported by an earlier-filed design application.

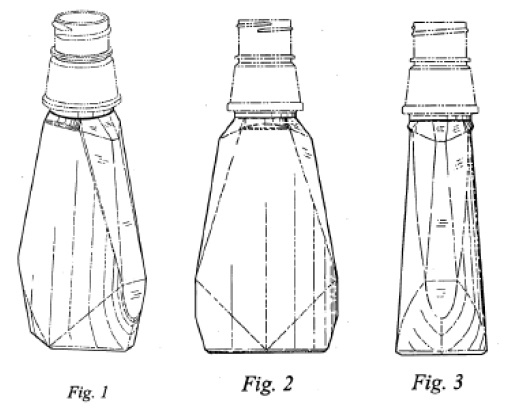

Owens, an inventor for The Procter & Gamble Company, filed a design patent application for a bottle, referred to herein as the '709 application, and that application ultimately issued as a design patent. The claimed design apparently covers the bottle design for the Crest® Pro-Health Care line of mouthwashes. Figures 1-3 of the '709 application are reproduced below.

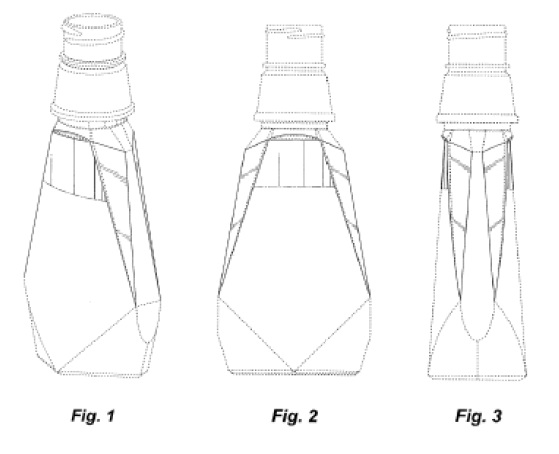

Subsequent to filing the '709 application, Owens filed the '172 application, which is a continuation of the '709 application, meaning that the '172 application relied on the '709 application for a filing date earlier than its actual filing date. The patentability of the '172 application hinged on whether it was entitled to the earlier filing date of the '709 application due to patent-barring sales of the claimed bottle that occurred more than one year prior to the actual filing date of the '172 application. Figures 1-3 of the '172 application are reproduced below.

The drawings of the '172 application contained two changes as compared to those of the '709 application: (1) they converted several solid lines to broken (a.k.a. “dashed”) lines, and (2) they introduced a broken line bisecting the pentagonal front panel. In design patents, broken lines indicate lines or boundaries that are optional, i.e., not required of a potentially infringing article, whereas solid lines are generally required of an article in order to infringe the patent. The case turned on whether the addition of the broken line bisecting the pentagonal front panel – resulting in only a portion of the pentagonal panel being claimed – was supported by the drawings of the '709 application, or whether it introduced impermissible new matter.

On appeal, the USPTO maintained its position that Owens must demonstrate, based on the content of the earlier '709 application, that he possessed the design for a bottle having a trapezoidal section occupying part, but not all, of the center-front panel. Relying on an earlier decision in In re Daniels, Owens argued that he did not need to prove support for the partial trapezoidal section, because all portions of the pentagonal front panel -- which encompassed the trapezoidal section -- were clearly visible in the '709 application.

The Federal Circuit disagreed with Owens, stating that “[i]t does not follow from Daniels that an applicant, having been granted a claim to a particular design element, may proceed to subdivide that element in subsequent continuations however he pleases.” The court characterized the issue as whether a skilled artisan would recognize upon considering the '709 application that the trapezoidal top portion of the front panel might be claimed separately from the remainder of that area, and it agreed with the USPTO that she would not. Accordingly, the court affirmed the BPAI’s holding that the '172 application introduced new matter not supported by the earlier application, and hence, could not rely on the earlier filing date of the ‘709 application, rendering the ‘172 patent invalid.

The Federal Circuit went on to provide guidance on when an applicant could introduce an unclaimed boundary line where no boundary line existed previously. The court appears to have expressly authorized the introduction of an unclaimed boundary line (i.e., a broken line) in cases where it makes explicit a boundary that already existed, but was previously unclaimed in the original disclosure. However, the court indicated that the USPTO’s rule endorsing the addition of an unclaimed boundary line in circumstances where it connects the ends of existing full lines was tenuous. Thus, while the case provides some guidance on when the addition of unclaimed boundary lines is acceptable, further guidance from the USPTO is needed.

While In re Owens deals specifically with the issue of whether a continuation application is entitled to the benefit of the filing date of an earlier application, the same principles would logically apply to changes made to design patent application drawings mid-prosecution, e.g., through an amendment, where the introduction of new matter is similarly disallowed. To avoid the situation encountered in In re Owens, prior to filing an application, design patent applicants should consider the range of claim amendments that may be desired during the life of the patent application, and its progeny, and include multiple sets of drawings including various claimed and unclaimed features, and associated boundary lines. While it’s impossible to predict the future, this type of forethought may prevent the type of new matter rejection faced in In re Owens.