If you're active in the payments space, whether as an acquiring bank, processor, ISO, or a merchant that accepts credit or debit cards, you've probably encountered the concept of "Discount Programs." Such programs purport to allow merchants to recoup the cost of accepting payment cards without violating state laws prohibiting surcharges. But look carefully: Is that Discount Program actually a surcharge that violates surcharge restrictions?

Perhaps the better question is, who cares? With anti-surcharge laws being struck down around the country, does it even matter what the program is called or how it is structured? The answer is yes, it does matter. Even if surcharges were clearly legal on a nationwide basis, Visa and MasterCard (the "Networks") still have specific rules for merchants that choose to impose surcharges on customers.

Discount Programs

A "surcharge" is typically defined as any means of increasing the regular price of goods or services for a cardholder that is not imposed upon customers paying by cash, check, or similar means. Laws that prohibit surcharges do not prohibit a merchant from offering a discount from the price of goods or services to encourage customers to pay by cash or other means, rather than using a credit card. However, the manner in which the merchant applies the "discount" is critically important.

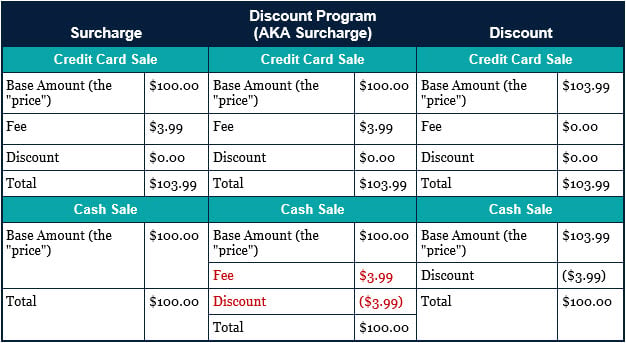

A typical program involves a service fee or other charge that is added to the cost of all purchases and then later waived or "discounted" for customers who pay by cash, check, or other method that is not a credit card. The argument is that the "discount program" creates discounts to the purchase price for cash, rather than increases for credit cards. However, this discount program doesn't actually create discounts; rather, it raises the posted price of all goods or services through a service fee that is then waived for non-card purchasers. The result is not a discount, but a fee charged at the point of sale only to customers paying by credit card – in other words, a surcharge. See the chart below:

The fact that each scenario above has the exact same economic result is the basis for the lawsuits challenging surcharge laws in several states.

Recent Surcharge Rulings

Currently, ten states have laws prohibiting credit card surcharges. Surcharge prohibition laws in several states have been challenged in recent lawsuits on constitutional and other grounds. Many of these cases proceed under the argument that laws prohibiting surcharges, but allowing discounts, impermissibly regulate speech by regulating the communication of prices, not the prices themselves. In the last twelve months, the laws in California, New York, and Texas have provided a range of outcomes:

- California: In Italian Colors v. Harris, a Federal District Judge ruled that a law prohibiting surcharges but allowing cash discounts was unconstitutional. The California Attorney General's Office appealed the decision to the Ninth Circuit, which affirmed the district court's ruling in January 2018. According to the California attorney general, the ruling applies only to the specific parties to the case, and "Therefore each use of a credit card surcharge would need to be evaluated based on its own particular facts."

- New York: In March 2017, the U.S. Supreme Court in Expressions Hair Design v. Schneiderman ruled that New York's surcharge prohibition is an attempt to regulate speech (not prices). The Court remanded the case to the Second Circuit for further proceedings to determine whether New York's law impermissibly regulates speech. The Second Circuit in turn referred the question to the New York Court of Appeals, which decided on October 23, 2018 that merchants may characterize the price difference as a surcharge as long as the merchant posts the total credit price. For more information, see our article on this case here.

- Texas: In 2016, the Fifth Circuit affirmed the district court's decision in Rowell v. Pettijohn (later re-styled Rowell v. Paxton) upholding the Texas surcharge prohibition. The U.S. Supreme Court denied the plaintiff's writ of certiorari, instead remanding the case to the district court for proceedings consistent with its decision in Expressions. Ultimately, the district court reversed its prior position and in August, 2018, held that the Texas surcharge prohibition is unenforceable as an unconstitutional speech regulation.

Card Brand Rules

Even in cases where surcharges are legal, merchants and other payments service providers should be aware that the card brands impose their own restrictions, including:

- Registration: The Networks require a merchant to provide notice of its intent to impose surcharges to each network and the merchant's processor at least 30 days in advance.

- Disclosure Requirements: Merchants must clearly and prominently disclose to consumers any surcharge that will be assessed, including (1) the exact amount or percentage; (2) a statement that the surcharge is assessed by the merchant and is applicable only to credit card transactions; and (3) a statement that the surcharge amount is no greater than the amount paid by the merchant to its payment processor for processing the transaction.

- Pricing and Structure: Surcharges must be calculated at the brand or product level according to certain complex Network rules, but in all cases, they must be less than the maximum permitted cap, which is currently 4%.

A typical Discount Program would not meet these requirements, and, in a recent newsletter, Visa stated that "Models that encourage merchants to add a fee on top of the normal price of the items being purchased, then give an immediate discount of that fee at the register if the customer pays with cash or debit card, are NOT compliant with the Visa Rules and may subject the acquirer to non-compliance action."

Based on trends in recent case law, surcharges may be legal in all or nearly all states in the next few years. Rather than adopt a program that mischaracterizes a surcharge as a discount, merchants and other service providers would be better served by calling a surcharge a surcharge and developing a program that meets the Network requirements.

For more information, please contact any of the authors.