Introduction

There is always a line at Starbucks. That line means steady rents for landlords leasing to Starbucks tenants. A common real estate fund model is to "roll up" multiple freestanding, single-tenant commercial properties, like Starbucks, into a single asset that accomplishes an economy of scale, diversifies risks, and achieves a portfolio size that is palatable to investors with real money. These funds can offer investors steady cash flows, capital appreciation, tax-sheltered returns from depreciation deductions, and portfolio diversification away from stocks and bonds.

For emerging fund managers in this space, the structuring legalese can be confusing; but it is important. Legal structures directly impact investor returns and risk management profile. In general, tax considerations are foundational to any real estate fund legal structure. The goal of these tax considerations is simple: minimize taxes on investor earnings and management compensation without undue complexity. This article walks the reader through a basic structuring analysis.1

The Economics of Real Estate Funds

Before we wade into the tax pond, let's review a typical real estate fund's economics in broad strokes.

A typical U.S. real estate fund will have a limited life span of not more than 10 years. Its life cycle will comprise an initial investment-reinvestment period during which the fund will seek out and purchase real property that meets the investment criteria set out by its sponsor (a/k/a "general partner" and/or "managing member"), followed by a longer holding period, during which the fund will seek to increase the value of the real property (whether by mere passage of time or through improvements made to the real property) and, last, a liquidation period when the properties are disposed of and the cash is distributed to investors. Often, the fund will have one or more optional extension periods to deal with unexpected changes in investment values or disposition strategies.

The limited life of a U.S. real estate fund often is ascribed to the fact that real estate is very illiquid, not homogeneous, typically cyclical, and sensitive to economic conditions and investor sentiments. A sponsor generally will identify what he perceives to be a niche in the real estate valuation for a particular type of property during a particular period, and devise an investment strategy to exploit the niche.

Given the characteristics of real estate noted above, however, a real estate fund will be able to identify only so many investment opportunities that fit the fund's investment strategy during any given period. For example, some funds will attempt to exploit perceived valuation distortions, while some will seek to increase the property value through turn-around strategies, and others will seek stable, income-producing properties. In addition, investing in real estate takes a significantly greater amount of time and money compared with other assets, especially liquid securities.

Because of this "lead-in" and "lead-out" nature of a U.S. real estate fund's activities, a U.S. real estate investment fund rarely changes its investment strategy midcourse, barring unforeseen circumstances, such as a radical shift in asset values. Often a fund will not be able to change its investment strategy without investor consent, since investors invested on the basis of that strategy. Thus, when the real estate investment landscape changes significantly after a fund is formed, the sponsor typically will simply cease making investments from one fund and form a new fund rather than try to change the direction of an existing fund.

The same peculiarities of real estate investment also require that a sponsor heavily regulate the cash flows into and out of a fund to manage the fund's liquidity and valuation. A typical real estate fund will raise funds through subscriptions made by investors in one or more closings of limited partnership interests (or limited liability company membership interests) over a limited period, once the sponsor identifies an investment strategy and makes his business case to potential investors through the offering materials (e.g., the "Private Placement Memorandum" or PPM). The PPM lays out the terms of the offering. The PPM is often presented to potential investors at meetings and presentations – called "road shows," subject to the applicable requirements of the securities law (e.g. the general solicitation and advertising rules).

The first one or two investors often get preferential treatment and are called "seed investors." Investors coming in through later closings typically pay an interest factor to compensate the early birds for footing the bill for the first investments. New investors will not be allowed into the fund after the investment-reinvestment period has ended.

Investors will not fund all of their capital commitments in their subscriptions upfront. Instead, they gradually fund the investments as they are identified and purchased in accordance with the fund's investment criteria. Once invested, investors typically will not see the bulk of their funds until the back end and, therefore, typically will expect a minimum rate of return to compensate for the time value of their invested money, generally known as the "preferred return."

An investor generally will not be able to receive distributions, or redeem its interests in the fund, or withdraw from it, ahead of other investors, unless a compelling legal or regulatory justification (often the tax status of the investor being jeopardized without the withdrawal) exists. An investor will not be able to sell or otherwise transfer its interest in the fund without the consent of the sponsor.

While there are a myriad of ways to "slice and dice" the way investment proceeds are distributed among the investors and the sponsor, often a real estate fund will allocate cash pursuant to a distribution "waterfall" (either on a per-investment or the aggregate basis) that identifies the timing, amount, and priority of each distribution. Generally, a fund will pay investors, first, a preferred return on the invested capital, then a return of capital, and then divide the remaining funds between the investors and the sponsor.

The sponsor's share of these remaining proceeds is often called "carry" or "promote," which sometimes is subject to a "holdback" or "clawback" obligation to ensure appropriate promote sharing based on the economic performance of a fund during its entire life cycle. This right to carry or promote often is called "carried interest" or "promote interest" or "sweat equity" and, in tax jargon, "profits interest."

Often, because of the complexity of tax rules, actual tax liability of an investor for an investment in a U.S. real estate fund will differ from the investor's actual amount and timing of cash receipts. Therefore, frequently, a fund will build in the concept of a "tax distribution" to help investors pay their taxes on taxable income allocated to them ahead of the actual receipt of corresponding cash. Such tax distribution is generally structured as an advance against the recipient's share of regular distribution that will come later, similar in concept to loaning to self-employed individuals to pay their estimated taxes during the course of a year before reconciliation through the year-end tax return.

A sponsor typically will earn this promote, plus a management fee (to pay for and reimburse its management and operating expenses). The management fee is typically computed as a percentage of the capital commitment during the investment-reinvestment period and, afterward, as a percentage of the invested capital, which may or may not include any leverage employed in making the investments. In addition, investors may ask the sponsor to make its own capital investment on the same terms as the investors, to have some "skin in the game."

Hypothetical Example

Let's assume a hypothetical example. Alejandro Java, a 35-year-old graduate of the Michigan Ross School of Business, wants to leave his job at Blue Corners Capital to launch his own U.S. real estate fund – "the Coffee Fund."

Alejandro has identified 30 properties in Illinois and Michigan under long-term leases with Dunkin Donuts tenants. Alejandro believes he can add immediate value by the purchase and consolidated management of all 30 properties. To do so, Alejandro needs capital. Specifically, he needs $150MM because he has valued the 30 properties at an average of $5MM each. Assuming that he can finance the acquisition price with 60% bank debt, Alejandro needs to raise $60MM of equity capital.

Alejandro prepares the PPM and other offering materials and travels on a road show around the world to meet with select investors. He meets privately with potential investors and finally reaches commitments with the following three investors, the "seed investors," for the first closing of his offering:

- Jay Gatsby, a resident of Long Island, NY - $24MM

- Silvio Bellini, a resident of Italy - $24MM

- Maple Leaf Pension, a Canadian pension fund - $12MM

Because of his stellar presentation, Alejandro will not be required to contribute his capital to the Coffee Fund (thus, no "skin in the game") and will receive a 20% promote and a 2% management fee.

The Coffee Fund will have a life of 10 years, with two 1-year extensions at the sponsor's disposal. The first 3 years will be its investment-reinvestment period, during which it intends to acquire the 30 Dunkin Donuts properties. The fund will hold the properties for appreciation due to traffic increase in their geographic areas and plans to start their sales in year 8 of the fund's life until all of the investments are sold and the fund is liquidated in year 10.

Alejandro is elated, but does not want to pursue further capital through additional capital commitments at this point and wants to begin working right away. How should the Coffee Fund be structured to make his business case as enticing as it was? Let's look at the most often used legal structure for U.S. real estate funds.

Legal Structure

Most, if not all, of U.S. real estate funds are organized as partnerships and, to a lesser extent, as limited liability companies under the laws of a state of the United States. Delaware is the default state of choice in which to form a U.S. legal entity for transacting business and investments within the United States because Delaware has the most sophisticated corporate governance laws (e.g., laws relating to fiduciary duties of directors, officers, and general partners to shareholders and limited partners) and an efficient court system. Delaware is not selected for tax reasons.

The choice of partnership form is principally due to its "flow-through" nature for U.S. federal income tax purposes, which will be discussed later. While the limited liability companies have gained popularity in recent years, a limited partnership is still widely popular, because of many preferential tax and legal landscapes that have existed at the state and local levels governing real estate investments for many years.

A Delaware corporation (commonly known as a "C corp"2) is not used as the legal entity of choice for a U.S. real estate fund (or any private equity or hedge fund) because investors in a C corp are subject to "double taxation" in the U.S.3 To avoid "double taxation," most U.S. real estate funds are structured using a "flow-through" entity (e.g., a state law partnership or limited liability company, classified as a partnership for income tax purposes), including ones that invest through REITs.

This article discusses four commonly used structures: (A) a limited partnership, (B) a corporate blocker, (C) a corporate blocker with leverage, and (D) a REIT.

(A) Delaware Limited Partnership

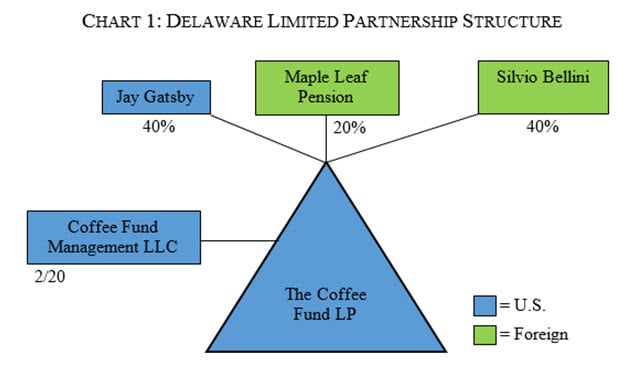

In our example, Alejandro could structure the Coffee Fund as a Delaware limited partnership ("Coffee Fund LP"), since the fund's investments will be made in the United States.4 Under this structure, Jay Gatsby, Silvio Bellini, and Maple Leaf Pensions would contribute capital to Coffee Fund LP in exchange for limited partnership interests in Coffee Fund LP. See Chart 1 below.

As mentioned above, partnerships are "flow-through" entities for U.S. federal income tax purposes. Thus, unlike corporations, partnerships are not subject to income taxation at the federal level. Rather, each item of income, gain, loss, deduction, and credit (collectively, "Income Items") of the partnership "flows through" to the partners and is reported on the partners' individual tax returns for the year. For each of its taxable years, a partnership files an informational tax return: IRS Form 1065 (U.S. Return of Partnership Income). Attached to IRS Form 1065 are Schedule K-1s for partners allocating to the partners their distributive shares of the partnership's Income Items for the taxable year.

The theory of "flow-through" taxation is that partnerships are conduits through which individual partners come together to perform an activity in the aggregate. As a result, the U.S. income tax rules governing partnerships (subchapter K of the Internal Revenue Code) require that the partnership's Income Items be allocated among the partners consistent with how the partners have decided to share in the underlying partnership economics. The dense tax boilerplate found in the partnership and limited liability company agreement of a typical U.S. real estate fund is designed to ensure compliance with these complex tax rules.

Because of the "aggregate" theory of partnerships, foreign investors may be reluctant to invest directly in partnerships operating a U.S. trade or business, as explained below.

(i) U.S. Investors

Turning the page back to the investors, we see that Jay Gatsby is likely content investing in a Delaware limited partnership. Jay Gatsby would receive a Schedule K-1 from Coffee Fund LP each year, allocating to him his share of Income Items (i.e., income, gains, losses, deductions, and credits). These Income Items would be reported on his IRS Form 1040 (U.S. Individual Income Tax Return) filed jointly with his wife, Daisy Fay Buchanan.5 Allocated ordinary income and short-term capital gain would be taxed at normal graduated rates up to 39.6%, at the federal level. Allocated long-term capital gains would be taxed at the current preferential rate of 20%, plus the 3.8% NII tax. As compared to a corporate structure, Jay Gatsby is likely content investing in a Delaware limited partnership.

(ii) Foreign Investors

The tax treatment of Alejandro's foreign investors, Maple Leaf Pensions and Silvio Bellini, is more complicated for three reasons:

- These investors generally will be taxed on a "net basis" (like Gatsby).

- If the foreign investor is a corporation, it will pay an additional 30% branch profits tax on its after-tax income.

- Foreign investors that are resident in jurisdictions with which the U.S. has entered into income tax treaties may be entitled to treaty benefits, which usually include exemption from the branch profits tax or reduction in the branch profits tax rate.6

The purpose of the branch profits tax is to prevent foreign corporations from avoiding "double taxation" by conducting business in the U.S., but not through a corporate subsidiary (i.e., through a branch), since dividends paid by a U.S. corporate subsidiary to a foreign parent are subject to a 30% federal withholding tax. Consequently, the branch profits tax rate matches the withholding tax rate on dividends of 30%, subject to treaty elimination or reduction. As Maple Leaf Pensions (but not Bellini) is a corporation for U.S. income tax purposes, Maple Leaf Pensions would owe an additional 30% branch profits tax on its after-tax income – essentially making Maple Leaf Pensions (unlike Gatsby) tax agnostic between investing in a U.S. corporation or U.S. partnership.

There is, however, another layer of complexity when dealing with foreign investors. Foreign investors resident in jurisdictions that have entered into income tax treaties with the U.S. may be eligible for elimination or reduction of the federal-level taxes under the treaty. Some old U.S. tax treaties provide for complete exemption from the branch profits tax, while many recent U.S. tax treaties extend to branch profits tax the same elimination or reduction in withholding tax on dividends.

Whether a foreign investor is eligible for treaty benefits generally depends on whether the U.S. has a tax treaty with the foreign investor's tax residence under local law. In our example, Maple Leaf Pensions and Silvio Bellini are residents of Canada and Italy, respectively, and the United States has income tax treaties with these two countries. Both treaties significantly reduce the dividend withholding tax rate (and the branch profits tax rate) from 30% to 5%, because the Coffee Fund will invest in U.S. real estate. This rate reduction significantly mitigates the burden of "double taxation." For example, because of these treaty benefits, if Silvio Bellini's investment was made into a U.S. corporation, his combined effective tax rate would be only 38.25% (not 50.4%).7 Readers paying careful attention will have noticed that this rate does not include the 3.8% NII tax, as the NII tax generally does not apply to income earned by foreign investors.

Thus, there is no meaningful difference in effective U.S. federal tax rates between Bellini and Maple Leaf Pensions on rental and other ordinary income of the fund (39.6% vs. 38.25%), but there is still a pretty big difference on any long-term capital gains (i.e., gain from the sale of capital assets held for more than one year) generated by the fund (23.8% vs. 38.25%).

However, that is not the end of the story for Maple Leaf Pensions. Many income tax treaties provide for favorable treatment for pension arrangements that meet certain criteria. If Maple Leaf Pensions can demonstrate that it is a qualifying pension fund under the U.S.-Canada income tax treaty, it may escape the branch profits tax altogether and be subject only to the 35% federal corporate income tax.

(iii) U.S. Tax Compliance

Putting aside the rate differences, foreign investors frequently are loath to invest in a U.S. flow-through entity operating a U.S. trade or business, because it requires them to a file U.S. income tax return: U.S. Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Form 1120-F (U.S. Income Tax Return of a Foreign Corporation) or Form 1040-NR (U.S. Nonresident Alien Income Tax Return). As noted above, partnerships are tax conduits such that their income and loss "flow through" to the partners, and the partners must file U.S. income tax returns reporting this income. If the foreign partner would not otherwise be required to file a U.S. income tax return, the receipt of such "flow-through" income triggers this new obligation.

A U.S. flow-through entity, such as Coffee Fund LP, will have an obligation to periodically withhold and remit to the IRS an estimated tax with respect to each foreign investor, based on the investor's distributable share of the fund's taxable income and gain. Such withholdings are treated as actually having been distributed to the investors for purposes of the distribution waterfall. A foreign investor will be required to file an income tax return after the close of each year, where it reconciles the tax withheld with the actual tax liability for the year. U.S. income tax return filers, therefore, become subject to the investigatory and subpoena powers of the IRS.

In contrast, U.S. corporations are not flow-through entities and are responsible for filing their own U.S. income tax returns (IRS Form 1120, U.S. Income tax Return) and paying their own taxes. Dividends paid by a U.S. corporation to foreign investors, while taxable in the U.S., are handled through withholding at the source, so foreign investors do not need to file a U.S. income tax return to report dividend income to the U.S. tax authorities.

(iv) Sponsor's Share of Fund's Profits

Generally, the carry or promote paid to the sponsor will be structured so that it is taxed in a manner that is similar to the way in which the investors who actually put up the cash are taxed on the distributions from the same investment. Currently taxation of "carried interests" has received significant negative publicity because of the lower tax rates it tends to generate, and there are ongoing discussions about different ways to change the law, so that it is taxed more like service income at higher tax rates.

B. Corporate Blocker

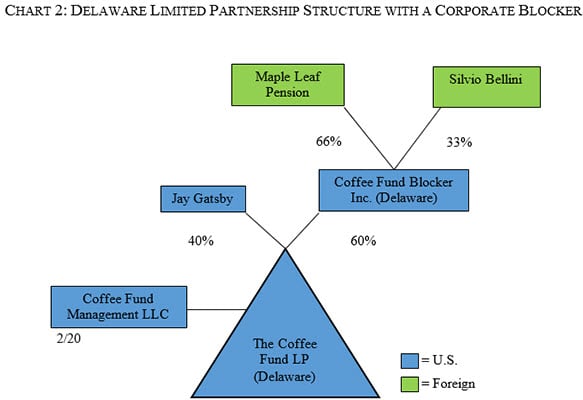

Often U.S. tax-exempt investors or foreign investors (Maple Leaf and Bellini) will prefer to invest in a U.S. real estate fund through a "blocker" corporation, as shown below:

The corporate blocker for a U.S. real estate fund typically is formed as a U.S. corporation, but there are many variations to this approach. A U.S. tax-exempt investor may use a corporate blocker if the investment strategy is likely to yield income and gain that is taxable as "unrelated business taxable income" (UBTI). UBTI is income that is generated in a manner and purpose inconsistent with the tax-exempt purpose of the investor, and is taxable at corporate tax rates. Generating UBTI can create perception issues and, in limited instances, result in tax penalties and/or the disqualification of tax-exempt status. For foreign investors, investing through a blocker also avoids their having to file a U.S. income tax return.

Thus, the foreign investors' income from the Coffee Fund is "blocked" from direct U.S. income taxation and reported by the U.S. corporation (the "Coffee Fund Blocker"). Earnings distributed from Coffee Fund Blocker to Bellini and Maple Leaf are taxed again as a corporate dividend from a U.S. corporation to a foreign person. Interposing a corporate blocker may result in increased U.S. tax cost to foreign investors, depending on the facts and circumstances.

In our example, Bellini's effective federal tax rate on ordinary income actually goes down slightly, from 39.6% to 38.25%, while his U.S. federal tax for long-term capital gain jumps from 23.8% to 38.25%. Since the Coffee Fund is counting on the economy of scale and better management fetching higher valuations (i.e., capital appreciation), Bellini's U.S. federal tax cost could increase significantly if he invests through the Coffee Fund Blocker.

In addition, because of the compliance costs, such as annual separate accounting, tax, and registration costs, a corporate blocker is a high-maintenance proposition for some foreign investors. Bellini, being a man of numbers, decides that the Coffee Fund Blocker is not warranted, especially since Italy has a tax system comparable to that of the U.S., allowing a degree of tax credit for income tax paid overseas, defraying a significant portion of his U.S. tax cost.

C. Corporate Blocker with Leverage

Often a corporate blocker will be funded with a combination of debt and equity from the foreign investors. U.S. tax-exempt investors avoid this form because this can easily turn their investment income into UBTI for technical reasons beyond the scope of this article. This debt-equity package (often known as "interest stripping") is still popular with foreign investors, because interest on debt can be used to offset the taxable income of the corporate blocker at the federal, state, and local levels, which, when combined, represents a significantly higher tax rate than the withholding tax on interest paid to the foreign investor. In other words, the U.S. tax benefit of the interest expense deduction often exceeds the U.S. tax cost on the corresponding interest income. If the foreign investor qualifies for an exemption from, or reduction of, the withholding tax on the interest, this tax arbitrage can result in even higher savings for foreign investors.

However, because of a series of rules enacted and adopted to curb interest stripping, as well as significantly enhanced documentation and reporting requirements, this form of interest stripping is not as popular as it once was. As a general rule, foreign investors cannot leverage the corporate blocker to an extent greater than a loan an unrelated lender would have made against the same assets of the corporate blocker.

In our example, Maple Leaf Pension ultimately decides against an interest stripping strategy because the tax savings are not significant enough to justify the leverage, because of limitations on interest deductions under U.S. tax rules.

D. REIT

A U.S. real estate fund often invests with a real estate investment trust (REIT) or uses a REIT as a legal vehicle for a joint venture with a tax-exempt investor or a foreign investor. A REIT is, in summary, any U.S. business entity that acts like a mutual fund with a real estate concentration. To qualify as a REIT, the U.S. business entity has to make an election to be taxed as a REIT, and satisfy on an ongoing basis a number of ownership diversification, real estate asset and income concentration, active business prohibition, and distribution requirements, among others. When it does, just like a mutual fund, it will be treated as a corporation that does not pay corporate income tax on its distributed income.

A REIT is generally not suitable as the primary vehicle for a U.S. real estate investment fund because of the numerous and technically difficult qualification requirements. For example, the rigid distribution rules applicable to a REIT will be inconsistent with the flexibility required of a typical real estate fund distribution waterfall.

Instead, a REIT is often used to create investment opportunities with tax-exempt investors and foreign investors because, like a corporation generally, it can serve the function of a corporate blocker or reduce the tax cost from investment in significant ways. For example, a REIT may be a suitable joint venture vehicle for a real estate fund that seeks to team up with a pension fund to acquire a large hotel that the fund could not acquire alone because of its size, whereas a pension fund will shy away from direct investment in a hotel because of the UBTI concerns. Properly structured, a hotel REIT will shield the pension fund from UBTI concerns while allowing the real estate fund to make an investment that it otherwise could not have made.

Similarly, a REIT will be an enticing opportunity for a foreign investor if the U.S. real estate fund does not have significant foreign investor ownership and is willing to take more than a 50% interest in the REIT. In such case, again, properly structured, the foreign investor will be able to take advantage of a special rule that allows it to exit its investment tax-free through the sale of its REIT stock (the so-called domestically controlled REIT rule), while allowing its U.S. real estate fund partner an investment opportunity that it otherwise would not have been able to close.

In our example, the Coffee Fund most likely will not be interested in teaming up with a REIT, because it has sufficient funds raised from the seed investors for its intended investment goal: to acquire a 30-property Dunkin Donuts portfolio in the first 3 years of its life. Moreover, because the Coffee Fund has significant foreign investor ownership (i.e., more than 50%), it would not qualify for the "domestically controlled REIT" rule noted above.

Thus, one can see from this example how a structuring analysis is highly fact-dependent, and it is difficult to distill general rules of thumb.

Tax Law Changes

Tax law will undergo many changes this year and in the near future, as the new administration and new Congress will try to "fix" laws and regulations that are perceived as "unfair" or "not working." For example, there is a great debate regarding how a carried interest is taxed, while an entirely new idea of creating a new tax rate for income earned through flow-through entities is also being entertained. Thus, the way a U.S. real estate fund is structured may change soon, in reaction to how tax law changes.

Conclusion

The aggregation of triple-net leased real estate can produce a very attractive real estate fund model. As illustrated by the Coffee Fund example, there is no "one size fits all" approach to structuring a U.S. real estate fund. The proper fund structure will depend on the facts and circumstances. As indicated above, the key facts and circumstances include (i) investor type (e.g., taxable versus tax-exempt), and (ii) the business strategy of the fund. In addition, compliance with applicable securities laws is a critical component of a successful fund launch. Although launching your first real estate fund in the U.S. is an extremely complex process, we hope that this article gives the reader a better understanding of the analysis that goes into structuring a U.S. real estate fund.

[1] This writing was prepared for marketing purposes and does not constitute tax opinion or advice to any taxpayer. Each taxpayer should consult its own tax advisor for the application of the tax laws to its own facts. In addition, this writing is based on current U.S. federal income tax law, and the authors will not update any reader on any future changes, including those with retroactive effect, in U.S. federal income tax law. This article does not address any state, local, foreign, or other tax laws, except as used in the writing for illustrative purposes only.

[2] The term "C Corp" comes from the fact that, without a special entity tax classification election, it is taxed pursuant to Subchapter "C" of the Internal Revenue Code.

[3] Specifically, U.S. corporations are taxed at the entity level on their worldwide income, currently at rates as high as 35% at the federal level. After being taxed at the corporate level, corporate earnings are taxed again when distributed to shareholders as a dividend. Dividends from a C corp in the hands of an individual investor currently are taxed at rates as high as 20% at the federal level, and are subject to an additional 3.8% Medicare tax on net investment income (the NII tax) that exceeds an income threshold. This translates into a combined 50.47% effective tax rate at the federal level on the fund's income.

[4] Forming a Delaware limited partnership requires filing a Certificate of Limited Partnership with the Delaware Division of Corporations in accordance with the Limited Partnership Act of the State of Delaware.

[5] In this hypothetical, Gatsby and Daisy are married.

[6] For a list of countries that have an income tax treaty with the U.S. see https://www.irs.gov/businesses/international-businesses/united-states-income-tax-treaties-a-to-z.

[7] 38.25% = 35% (corporate income tax) + (1-35%)*5% (branch profits tax)